Long Story Short, ep. 8: An Unwritten Rule

Chatterbug’s new podcast, Long Story Short, covers beginners German for English speakers. Each episode is in German and English, and takes you on a journey. Listen as the characters navigate their way through chance meetings, miscommunications and surprises.

You can also listen on Apple or the RSS feed. Below is a transcript of the eighth episode.

Intro

HELENA: From Chatterbug and produced by Weframe Studios, you’re listening to Long Story Short – Lange Rede, kurzer Sinn, ein Podcast in Deutsch und Englisch. In Season One, we will focus on talking points we found to be most valuable for A1 German learners.

Our podcast coincides with topics in our curriculum at chatterbug.com. So, if you’re looking for a deeper dive into language learning, check us out there. For those of you following the Chatterbug curriculum, remember to look out for a few key themes today covering greetings and invitations, talking about the family, and, for when we can all get together again, organizing a barbecue.

Today’s episode is “An Unwritten Rule”, meaning “Eine unausgesprochene Regel”. For those of us who speak English as a first language, while it can be a major advantage, it also feels like an excuse to stay monolingual. But then, we miss out on whole other worlds of thinking, being, doing. What are we most worried about when trying on a new language?

An Unwritten Rule

[01:15]

TIM: Okay, can we go over this again?

I pressed. I was feeling the pressure. We were only a few minutes away from the big moment, but my girlfriend, Emma, wasn’t having any of it.

EMMA: Wenn du dich im Gespräch mit ihm wohlfühlen möchtest, dann musst du mit mir üben. Wir sprechen jetzt einfach weiter auf Deutsch.

TIM:

She had a point. You see, my first language is English, which, we all know, almost always means my only language is English. So, maybe this happened to me for my own good, karma, if you will.

Enter Emma. We met in London, but she just so happens to be German, a Berliner, to be exact. And for the first time in my life, I’m very aware of my Englishness, and we began to discuss the idea of traveling to Germany to meet her parents. She described them as foundational English speakers. They know what they have to, and for most of their lives, that meant not too much. And fair play to them; sounds a lot like someone else she knows. But here lay our problem, so I set about on my journey learning to speak German, which is how I landed many months later in a taxi, having just arrived in Berlin for Emma’s mother’s 60th birthday party.

Okay, dann eben auf Deutsch. Also, deine Mutter heiβt Julia, dein Vater Johann.

I wanted to be sure I had all the names right.

EMMA: Genau. Und meine Geschwister?

TIM:

She was checking.

Dein junger Bruder heiβt Lukas und deine Schwester Anika.

I confirmed.

EMMA: Perfekt! Gut gemacht! Ich werde dir alle anderen — meine Tanten, Cousins — vorstellen, wenn wir dort sind.

TIM:

Emma explained. Which reminded me:

Oh, ich hätte es fast vergessen, wie sind die Regeln dafür?

I asked.

Um andere Leute zu begrüβen.

She paused and then queried:

EMMA: Was meinst du?

TIM:

You see, I’d always been confused with how Europeans greet one another. In each country, it seems, the number of kisses varies, the cheeks differ, even the placement. I know it sounds laughable to some, but nobody teaches you this. It’s like an unwritten rule, the key that unlocks a continent of introductions.

Nun, wie viele Küsse? Und wo?

She let out a laugh.

EMMA: Nun, mein Dad würde sich über einen Handkuss freuen.

TIM:

She teased, grabbing my hand, bowing her head as she kissed it. She could tell I was serious, though, so attempting to disguise her amusement, she continued.

EMMA: Okay, okay. Also, in Deutschland sind es normalerweise zwei Küsse, einer auf jeder Wange.

TIM:

She once again lent over, demonstrating on me.

EMMA: Aber meine Mutter kommt aus einer kleinen Region in der Nähe von Berlin und wenn dort jemand zum ersten Mal die Familie kennenlernt, dann ist es für sie ein Zeichen von Höflichkeit, wenn man vor den beiden Küsschen auf die Wange, sie auf die Stirn küsst. Wenn du das tust, wirst du alle beeindrucken.

TIM:

I’d never heard of such a custom.

Wirklich? Nei ne?

But who was I to question years of tradition? On our arrival, I braced myself for a day of keeping up with the family, essentially, of trying to prove that Emma had chosen right. Just before we rang the bell, I told Emma how I was feeling.

Ich bin ziemlich nervös. Ich hoffe, sie mögen mich.

She looked nervous, too, and began to console me.

EMMA: Ja, okay, Tim. Du, wegen vorhin…

TIM:

In that second, though, the door flew open. She wasn’t able to finish her sentence. And I don’t know if it was the nerves, but I just dived in there. The moment her father appeared in the doorway:

Hi, ich bin Tim, und du bist sicherlich Johann. Ich freue mich sehr, dich kennenzulernen.

I announced and grabbed Emma’s dad by the shoulders and, as instructed, kissed him on the forehead and then once on each cheek. Instantly, however, it seemed something was wrong. What had I said? Johann paused for what felt like 10 seconds and then responded with:

JOHANN: Ach, wir sind schon beim Du, was?

TIM:

Oh, no, oh, no, in my rush, I’d forgotten the polite form in German. I stuttered trying to find the right wording, but in his eyes, I suddenly saw Emma. He had an expression that I’d only ever associated with her, a cheekiness, and the laugh that followed brought huge relief.

JOHANN: Das war nur ein Scherz. Du sprichst groβartig Deutsch. Willkommen in der Familie, Tim.

TIM:

I then remember Emma attempting to pull me aside. I guessed she was worried about my nerves. I seemed to be running on adrenaline, though, and gave her an “I got this” nod. One by one, Emma’s family members appeared in the hallway, each welcoming me so graciously. I make my way through introducing myself and, dutifully, as the newcomer, delivered their traditional address of a kiss on the forehead. But by the time I reached Emma’s brother, they were already handing me a drink.

LUKAS: Hi, Tim! Ich bin Emmas Bruder, Lukas. Es ist toll, dich kennenzulernen. Ich hoffe, du magst Berliner Weisse.

TIM:

I jumped up to plant my greeting on him.

LUKAS: Hoppla, habt ihr schon was getrunken?

TIM:

I wasn’t sure what he meant. But then, Emma’s mum, the one we were all there for, appeared in the crowd.

JULIA: Hallo Tim!

TIM: Ach, da ist sie ja!

I burst out from across the room. Everyone parted as I made my way over to her. I took Emma’s mom in my arms, kissing her forehead.

Herzlichen Glückwunsch zum Geburtstag, Julia. Es ist so nett von dir, mich in deinem Haus willkommen zu heiβen.

I beamed and surprised myself with how comfortable I was getting with all this PDA.

JULIA: Oh, danke schön.

TIM:

Julia uttered, touching her brow as my greeting lingered. Emma was right — she must be impressed. I was nailing it, and it felt good. She then turned, ushering over an old man I recognized to be Emma’s grandfather.

JULIA: Und hast du schon Emmas Groβvater kennengelernt?

TIM:

But before I could answer, Emma interrupted:

EMMA: Has du Hunger, Tim?

TIM:

Her words shot out. She seemed flustered.

Oh, äh, ja, habe ich, mein Schatz.

I replied confused, half answering Emma and half smiling at her grandfather. She suddenly seemed to be much more anxious than I was. Lukas then joined the conversation.

LUKAS: Toll, ich habe auch Hunger. Worauf hast du Lust? Isst du gerne Gemüse oder lieber Fleisch?

TIM: Ich mag beides.

I responded.

LUKAS: Cool! Und hat meine Schwester dich schon in die deutsche Küche eingeführt? Isst du gerne Schnitzel oder Sauerkraut?

TIM:

The food all sounded great, but why were you ignoring their relatives, I wondered to myself.

Ja, ich mag alles.

I replied, then attempted a return to their grandfather. But Emma swept in once again with:

EMMA: Cool, dann setz dich doch zu Lukas und mir. Das Essen sollte bald fertig sein.

TIM:

All I could do is wave in his direction as I was escorted away. Why had Emma suddenly become so guarded of her family? I needed to check in, so I asked her:

Was glaubst du? Wie läuft’s denn?

EMMA: Tja...

TIM

Emma started, but I wanted to assure her.

Falls du dir Sorgen machst, die Nerven sind weg. Ich glaube, es läuft gut, oder?

She looked hesitant for a second, but then agreed. It seemed she wasn’t over her own nerves yet, but as the day proceeded, it became better than I could have ever expected. It turns out I love German food, I love German beer, and love Emma’s family. I thought this would make Emma happy, too, but she grew wearier as each hour passed, as each new guest arrived. When the day’s events came to a close, I joined her in helping to clear up. In so many ways, it felt like a victory lap. But Emma still seemed off. Out of the people I thought I need to impress that day, I hadn’t expected it to be her.

Glaubst du, sie mögen mich?

I asked.

EMMA: Sie lieben dich.

TIM:

She said softly, but clearly still uneasy.

Emma’s mother then arrived, asking if I’d be able to lend her a hand with tidying up in the garden. I was reluctant to leave Emma like that, but perhaps this was a chance to redeem myself. As Julia and I collected cutlery amongst the remains of a celebration well spent, she began to speak.

JULIA: Es ist so nett von dir, dass du den ganzen Weg hierher gekommen bist, Tim. Wir freuen uns sehr, dich endlich kennenzulernen.

TIM:

She then walked across the lawn to me and placed her hands on my shoulders, rising up so we were level. She kissed me on the forehead and smiled. It was then that I recognized the heartfelt significance of their tradition. As we strolled towards the house, I turned to Julia.

Mir war nicht klar, dass man sich auf die Stirn küssen kann nicht nur um hallo zu sagen. Wann kann man es sonst noch tun?

Julia had used the greeting as a way to comfort me. Perhaps I could do the same for Emma? But then…

JULIA: Ich weiβ es nicht. Wann kann man es tun?

TIM:

Maybe I was misunderstanding her.

Entschuldigung, ich meinte die traditionelle Begrüβung aus deiner Stadt.

I explained.

JULIA: Aus meiner Stadt? Ich dachte, du sprichst davon, was bei dir Sitte zu sein scheint. Ein Kuss auf die Stirn, nicht wahr?

TIM: Our eyes widened in unison, baffled. As I began to put the pieces of this puzzle together, I glanced up to see Emma’s family standing at the end of the garden, watching us, Emma in the middle. The expression she’d worn on her face all day suddenly made sense. It wasn’t one of doubt, but of remorse. I’d been so focused on getting everything right, down to the detail, that I hadn’t been able to tell jest from genuine, let alone ridiculous from really bloody stupid. Emma had never meant for me to take her seriously, but I was a willing victim, unlike the strangers whose heads I’d been kissing all day. There I’d been making an utter fool of myself, but there they’d been, accepting me anyway. As the English speaker in the room, it’s easy to become complacent in a world that caters to your language, your comfort zone. I was no longer in mine, but I felt all the better for it. And that infamous family greeting, well, if it wasn’t a tradition then, it is now.

An Unwritten Rule – Breakdown

[11:11]

HELENA: And we’re back. You’ve just been listening to “An Unwritten Rule” or “Eine unausgesprochene Regel”. Hey, Danielle!

DANIELLE: Hey, Helena!

HELENA: We’re back for another breakdown.

DANIELLE: I’m ready.

HELENA: Are you? And this time the story was really sweet. It was about getting to know the family of your partner and the difficulties navigating different social situations and different cultural situations.

DANIELLE: Yeah, for sure.

HELENA: This one in particular — how to greet somebody. So, how do you greet people, Danielle?

DANIELLE: If I already know the person, then I go in for a hug.

HELENA: Nice.

DANIELLE: Okay, now, maybe not so much.

HELENA: Now you do the elbow bump.

DANIELLE: Now it’s the elbow bump, but if I don’t know them, then I immediately go to shake their hands.

HELENA: Okay.

DANIELLE: I think that’s the very American way to do it.

HELENA: Yeah, that’s, I think, also how I would do it in America.

DANIELLE: Yeah, now, where I’m from in the U.S. is in the south, and so, if it’s somebody who’s acquainted with someone we already know, then you go straight in for a hug. And so, we actually hug strangers in the south all the time.

HELENA: Yeah, I think you do that in California too.

DANIELLE: Oh, yeah?

HELENA: At least people my generation. Yeah, we give hugs. Sometimes, it’s a little bit like — Oh, we’re gonna… Are we gonna hug? Oh, we’re gonna hug? Okay, hugging.

DANIELLE: Yeah, in the south, they’ll just say “Get over here!” and they’ll grab you and give you a hug.

HELENA: Oh, that’s very friendly.

DANIELLE: Yeah.

HELENA: In Germany, it’s a little bit different.

DANIELLE: Yeah.

HELENA: And the story was really funny because it was a situation where the girlfriend was kind of playing a joke on her partner, being like, yeah, you have to kiss them on the forehead.

DANIELLE: Right, that was such a… It was a really funny joke, but he totally didn’t get it.

HELENA: Yeah, and I really loved how the family was playing along with it.

DANIELLE: That’s really nice.

HELENA: Because it was like a very… Like, I could totally picture these German families I’ve met that are like… they’re so careful, like, okay, this is a cultural thing, and they’re really like, okay, we’re gonna play along, this is who they are and we’re gonna accept them for that.

DANIELLE: Yeah.

HELENA: And I thought that that was something that I’ve seen in a lot of families I’ve met here. It was really lovely seeing it written like that.

DANIELLE: So, how is it that… How do you greet people? I feel like I still don’t know that even though I’ve lived in Germany for a couple of years now. How do Germans greet one another if they’re being introduced?

HELENA: So, there’s a few different ways. What I’ve had in Niedersachsen, where my mom is from, and, usually, if you don’t know somebody very well, sometimes you don’t even shake their hands. Sometimes, you just kind of stand in front of each other, kind of like bow your head a little bit or smile and wave.

DANIELLE: I think that’s what I usually do when I meet a new person here, just smile and wave.

HELENA: But if I’m greeting friends that I know very well, I actually do this single cheek kiss.

DANIELLE: Oh, okay.

HELENA: And a hug. Like, hug, we go in for a hug, and then, while you’re hugging, you kind of do the cheek.

DANIELLE: Just one, though.

HELENA: Yeah.

DANIELLE: But just touch the cheeks together, not an actual kiss on the cheek.

HELENA: Yeah, that’s something… When I was younger, I thought you actually kiss the cheek. So, I remember I was visiting my sister once at the university and I was saying hi to somebody and I actually kissed his cheek and he was like, “Okaaaay.” It’s just the… You touch cheeks.

DANIELLE: Yeah, but it is kind of hard to know what greeting is appropriate when you meet somebody, especially when it’s a cross-culture. I think it’s even difficult within a culture, but when you’re crossing cultures, it can be really, really tricky.

HELENA: Yeah, I have a few Greek friends, and whenever I go to meet their friends, it’s almost like you are going in for a legit kiss because you’re going the wrong direction and they’re going the way they usually go and you’re going the wrong way and you’re just like okay.

DANIELLE: I know, I know.

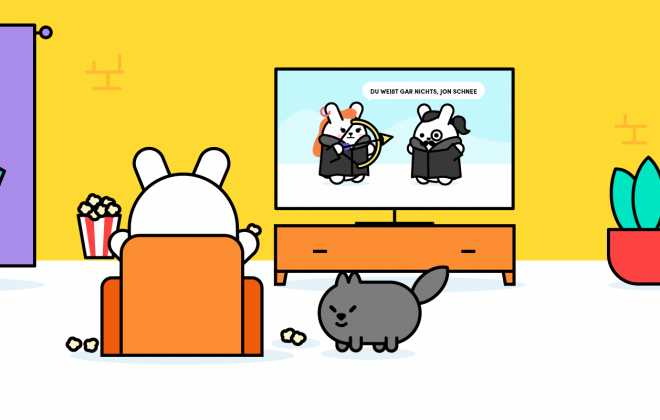

HELENA: And your face is getting really close. I saw other ways you can greet somebody in Germany. If you know them well, if they’re family, you can also do the two-kiss. Or a hug, of course, it’s also pretty common. So, the story is about a couple, Tim and Emma. And Tim is from England, and he’s about to get to know the family of Emma, who’s from Berlin.

DANIELLE: Yeah, it’s Emma’s mom’s birthday, right?

HELENA: Exactly, it’s her 60th birthday, and it’s like a big family fest. And Germans love to do big celebrations when somebody turns 60 or 50.

DANIELLE: Oh, okay.

HELENA: They get the whole family together, they have tons of food, and it’s like a really festive occasion.

DANIELLE: Oh, nice.

HELENA: I’ve been to a few of those parties myself, and it’s always really lovely to see everyone coming together. And, oh, my gosh, so much food! Like, Germans aren’t usually that foodie, but, I think, when they’re celebrating birthdays or anniversaries, they sometimes go all out.

DANIELLE: Okay.

HELENA: They go to like a nice restaurant, and it has usually a nice view.

DANIELLE: Oh, sweet!

HELENA: Yeah, so he gets to know the family, and Emma was joking.

DANIELLE: Well, he’s very nervous about meeting her family and so he asked what’s the proper way to greet them.

HELENA: Exactly.

DANIELLE: Right.

HELENA: And we’ll talk a little bit more later about what happened, but, basically, Emma makes a joke with him that he takes a bit too seriously. And, with that, let’s jump into the first dialogue.

DANIELLE: Okay, great.

TIM: Also, deine Mutter heiβt Julia, dein Vater Johann.

I wanted to be sure I had all the names right.

EMMA: Genau. Und meine Geschwister?

TIM:

She was checking.

Dein junger Bruder heiβt Lukas und deine Schwester Anika.

I confirmed.

EMMA: Perfekt! Gut gemacht! Ich werde dir alle anderen — meine Tanten, Cousins — vorstellen, wenn wir dort sind.

TIM:

Emma explained. Which reminded me:

Oh, ich hätte es fast vergessen, wie sind die Regeln dafür?

I asked.

Um andere Leute zu begrüβen.

She paused and then queried:

EMMA: Was meinst du?

TIM:

You see, I’d always been confused with how Europeans greet one another. In each country, it seems, the number of kisses varies, the cheeks differ, even the placement. I know it sounds laughable to some, but nobody teaches you this. It’s like an unwritten rule, the key that unlocks a continent of introductions.

Nun, wie viele Küsse? Und wo?

She let out a laugh.

EMMA: Nun, mein Dad würde sich über einen Handkuss freuen.

TIM:

She teased, grabbing my hand, bowing her head as she kissed it. She could tell I was serious, though, so attempting to disguise her amusement, she continued.

EMMA: Okay, okay. Also, in Deutschland sind es normalerweise zwei Küsse, einer auf jeder Wange.

TIM:

She once again lent over, demonstrating on me.

EMMA: Aber meine Mutter kommt aus einer kleinen Region in der Nähe von Berlin und wenn dort jemand zum ersten Mal die Familie kennenlernt, dann ist es für sie ein Zeichen von Höflichkeit, wenn man vor den beiden Küsschen auf die Wange, sie auf die Stirn küsst. Wenn du das tust, wirst du alle beeindrucken.

HELENA: All right, so Emma teaches Tim how to greet people.

DANIELLE: Yeah.

HELENA: But first, they talk a little bit about family because it’s really important to know the name of the people that you’re about to meet.

DANIELLE: And it’s okay to say the first name of a person’s parents?

HELENA: Yeah, in Germany it definitely is.

DANIELLE: Okay, interesting.

HELENA: In the U.S. you always have to say Mr. and Mrs.

DANIELLE: Yeah, exactly.

HELENA: But no, that’s not a thing in Germany.

DANIELLE: Okay.

HELENA: Yeah, if you’re family, you address people usually with “du”, and you address them by their first name. But we’ll actually talk a little bit more about that in Grammatically Speaking. What are “Geschwister”?

DANIELLE: They’re siblings, right?

HELENA: Exactly. And siblings, what are the two siblings you can have?

DANIELLE: Bruder — brother and Schwester — sister.

HELENA: Exactly.

DANIELLE: That’s where I always get a little bit confused, because there’s “Schwester” and then “Geschwister”.

HELENA: “Geschwister”, yeah, it is confusing. You would think that “Geschwister” means sisters.

DANIELLE: Sisters, yeah.

HELENA: But it doesn’t. Sisters are “Schwestern”.

DANIELLE: Yeah.

HELENA: Not “Geschwister”.

DANIELLE: And “Bruder” in the plural form?

HELENA: It’s “Brüder”.

DANIELLE: “Brüder”, okay. But together — “Geschwister”.

HELENA: “Geschwister”. Okay, so what’s some more family that we have? We have “Mutter” und “Vater”.

DANIELLE: Okay, mother and father.

HELENA: And we have “Tanten”.

DANIELLE: “Tanten” is aunts?

HELENA: Yes. “Cousins”?

DANIELLE: “Cousins” are cousins.

HELENA: Yes. And “Onkel”.

DANIELLE: Uncles, uncle.

HELENA: “Onkel” is the plural of uncle.

DANIELLE: Onkel.

HELENA: Yeah.

DANIELLE: Got it.

HELENA: So, Emma congratulates Tim on him knowing the names of his family and she says, “Gut gemacht!”

DANIELLE: Ach, ja.

HELENA: Or “genau”.

DANIELLE: Ja, gut gemacht.

HELENA: Both words express correctness.

DANIELLE: Okay. My son, he always says “toll gemacht” because, I think, it says it on one of his German programs. So, yeah, toll gemacht.

HELENA: Toll gemacht! Good job!

DANIELLE: So, what are some other useful words that you can say, other than “genau” or “gut gemacht”?

HELENA: You could say “prima”.

DANIELLE: Prima? Oh, okay.

HELENA: It’s a little old-fashioned, though. I think it’s not used as commonly as it used to be.

DANIELLE: Oh, okay. And I just learned one the other day. You can say “stimmt”, right?

HELENA: Stimmt.

DANIELLE: Stimmt, ja, stimmt.

HELENA: Stimmt. Das stimmt, Danielle. Which means that’s right. “Genau” is more like an expression of “yeah, exactly”.

DANIELLE: Oh, okay.

HELENA: “Stimmt” is like correct.

DANIELLE: Okay, yeah, I remember when I first got to Berlin, that was the first word that I noticed that Germans use a lot. Like, you hear “genau” a lot.

HELENA: It’s such a great word. It’s just… Put it wherever you want. Let’s take a look at two verbs that kind of have to do with “trennbare Verben”.

DANIELLE: Oh, okay.

HELENA: We have two verbs here. We have “vorstellen”. Do you know what that means?

DANIELLE: Like, to introduce?

HELENA: Exactly. So, the sentence is “Ich werde dir alle anderen vorstellen, wenn wir dort sind.”.

DANIELLE: Okay, so I’ll introduce you to the others when we’re there.

HELENA: Yes, and then, in the next sentence, it’s “Oh, ich hatte es fast vergessen. Was sind die Regeln dafür?”. So, the other verb is “vergessen”.

DANIELLE: Vergessen.

HELENA: “Vorstellen” and “vergessen”.

DANIELLE: “Vergessen” means to forget.

HELENA: Exactly.

DANIELLE: So, these are the verbs that are cut, and one part goes in the front and then the other part goes in the back.

HELENA: Jein, one is and one isn’t.

DANIELLE: Oh, okay.

HELENA: Yeah, and that’s why I wanted to draw attention to them, because it’s a little bit tricky. They sound like they would be both “trennbare Verben”, but they’re actually not. “Vorstellen” is “trennbar”, which, for example, you can say “ich stelle dich vor”.

DANIELLE: Oh, okay.

HELENA: I’ll introduce you. But “vergessen” is not a “trennbares Verb”. You cannot put the “ver” at the end.

DANIELLE: Oh, okay.

HELENA: “Ver” and “vor”.

DANIELLE: Okay.

HELENA: Two different prefixes.

DANIELLE: Okay.

HELENA: But, like we talked about last time, “vor” is… you can put it by itself, but “ver” you can’t.

DANIELLE: Okay, well, that’s a good way to remember that.

HELENA: So, now, let’s take a little bit of a closer look at a pretty dense part of the conversation where Emma is explaining how Tim can introduce the family.

DANIELLE: Oh, yeah, that chunk was a bit difficult for me.

HELENA: Yeah, it was a lot. So, let’s just go sentence by sentence.

DANIELLE: Okay.

HELENA: Take a closer look. So, she says, “Okay, okay. Also, in Deutschland sind es normalerweise zwei Küsse, einer auf jeder Wange.”

DANIELLE: So, normally, in Germany, two kisses on each cheek is normal.

HELENA: “Wange” means cheek.

DANIELLE: Cheek, yeah, Wange.

HELENA: So, funny thing about the word “Wange”, or the word cheek, is that in German you have two different ways of saying cheek.

DANIELLE: Oh, okay.

HELENA: You have the “Wange”, which always refers to the face cheek.

DANIELLE: Okay.

HELENA: And you also have “die Backe”.

DANIELLE: Die Backe.

HELENA: Which is the butt cheek.

DANIELLE: Oh, but it can also be the face cheek.

HELENA: It can.

DANIELLE: Oh, oh!

HELENA: It’s not as commonly used anymore to describe the face cheek.

DANIELLE: Okay.

HELENA: But you can say like red cheeks — rote Backen. There’s actually like a vitamin drink which is called Rotbäckchen.

DANIELLE: Oh, okay.

HELENA: Which means red cheeks.

DANIELLE: Okay.

HELENA: But it’s not referring…

DANIELLE: But not the butt cheeks.

HELENA: No.

DANIELLE: The face cheeks, okay. Huh!

HELENA: Yeah, it’s Tricky Tortoise.

DANIELLE: Okay, I think I’ll just use “Wange”.

HELENA: Just stick with “Wange”. Okay, so the next sentence is “Aber meine Mutter kommt aus einer kleinen Region in der Nähe von Berlin.”. Okay, so let’s stop there.

DANIELLE: Okay, so my mom comes from like a small region near Berlin.

HELENA: Yeah, probably in Brandenburg somewhere.

DANIELLE: Brandenburg, yeah.

HELENA: And the next sentence is “Und wenn dort jemand zum ersten Mal die Familie kennenlernt, dann ist es für sie ein Zeichen von Höflichkeit.”. So, let’s look at the first part. When you meet the family for the first time, then it’s a showmanship of politeness — “Höflichkeit”.

DANIELLE: Höflichkeit.

HELENA: Which means polite.

DANIELLE: Polite.

HELENA: Yeah. “Wenn man vor den beiden Küsschen auf die Wange, sie auf die Stirn küsst.”

DANIELLE: Okay, so before kissing on the cheek, you kiss the forehead.

HELENA: Yes, “Stirn” means forehead.

DANIELLE: Okay, but when I first heard this part, I actually was like, “Stern?” Because I was thinking “Stern” like star.

HELENA: Ah…

DANIELLE: Yeah, I mean, I watch a lot of German cartoons with my son and so, when I hear “Stern”, I was immediately like… But it’s “Stirn”.

HELENA: “Stirn” with an “i”.

DANIELLE: “Stirn” with an “i” meaning forehead.

HELENA: Yeah.

DANIELLE: Okay.

HELENA: I do actually really like the word “Stirn”. I think, you know, it’s like the heaven’s on your brain.

DANIELLE: Oh, that’s a nice way to make a connection.

HELENA: Yeah, it’s like that’s where the wisdom is. It’s like the third eye.

DANIELLE: Stirn.

HELENA: Yeah, the “Stirn”. Then she says, “Wenn du das tust, wirst du alle beeindrucken.”

DANIELLE: Didn’t catch that.

HELENA: Okay.

DANIELLE: Beeindrucken.

HELENA: Beeindrucken — you’ll impress everyone.

DANIELLE: Oh, okay.

HELENA: Yeah, it’s very similar. When you break down the word, it’s very similar to English. Impress, you know, to make a mark, to press into something.

DANIELLE: I see.

HELENA: And “beeindrucken”, you know, “drücken” means also to press.

DANIELLE: To press, oh, okay, “beeindrucken”.

HELENA: So, the words are very similar.

DANIELLE: Nice.

HELENA: Yeah.

DANIELLE: And so, he obviously then takes this seriously.

HELENA: Yes, and he’s like…

DANIELLE: Wirklich?

HELENA: I’m gonna kiss all those foreheads. You’re not gonna be ready for it.

DANIELLE: He’s like, you know, I don’t necessarily get it, but I’m gonna go with it.

HELENA: Yeah.

DANIELLE: Which is kind of the pressure that you feel, right, especially when you’re meeting the family of somebody that’s from a different culture. You really want to make sure you get it right, and so you might overdo it just because you really are trying to actually be really polite and show them that you care and that you are concerned about doing the right thing in their culture. So, I totally understood where he was coming from. But, yeah, he was a bit overzealous, wasn’t he?

HELENA: Yeah, he wasn’t really taking up any of the cues, was he? Let’s listen to the next part then.

DANIELLE: Okay.

TIM: Hi, ich bin Tim, und du bist sicherlich Johann. Ich freue mich sehr, dich kennenzulernen.

I announced and grabbed Emma’s dad by the shoulders and, as instructed, kissed him on the forehead and then once on each cheek. Instantly, however, it seemed something was wrong. What had I said? Johann paused for what felt like 10 seconds and then responded with:

JOHANN: Ach, wir sind schon beim Du, was?

TIM:

Oh, no, oh, no, in my rush, I’d forgotten the polite form in German. I stuttered trying to find the right wording, but in his eyes, I suddenly saw Emma. He had an expression that I’d only ever associated with her, a cheekiness, and the laugh that followed brought huge relief.

JOHANN: Das war nur ein Scherz. Du sprichst groβartig Deutsch.Willkommen in der Familie, Tim.

TIM:

I then remember Emma attempting to pull me aside. I guessed she was worried about my nerves. I seemed to be running on adrenaline, though, and gave her an “I got this” nod. One by one, Emma’s family members appeared in the hallway, each welcoming me so graciously. I make my way through introducing myself and, dutifully, as the newcomer, delivered their traditional address of a kiss on the forehead. But by the time I reached Emma’s brother, they were already handing me a drink.

LUKAS: Hi, Tim! Ich bin Emmas Bruder, Lukas. Es ist toll, dich kennenzulernen. Ich hoffe, du magst Berliner Weisse.

TIM:

I jumped up to plant my greeting on him.

LUKAS: Hoppla, habt ihr schon was getrunken?

TIM:

I wasn’t sure what he meant. But then, Emma’s mum, the one we were all there for, appeared in the crowd.

JULIA: Hallo Tim!

TIM: Ach, da ist sie ja!

I burst out from across the room. Everyone parted as I made my way over to her. I took Emma’s mom in my arms, kissing her forehead.

Herzlichen Glückwunsch zum Geburtstag, Julia. Es ist so nett von dir, mich in deinem Haus willkommen zu heiβen.

I beamed and surprised myself with how comfortable I was getting with all this PDA.

JULIA: Oh, danke schön.

TIM:

Julia uttered, touching her brow as my greeting lingered. Emma was right — she must be impressed. I was nailing it, and it felt good. She then turned, ushering over an old man I recognized to be Emma’s grandfather.

JULIA: Und hast du schon Emmas Groβvater kennengelernt?

TIM:

But before I could answer, Emma interrupted:

EMMA: Has du Hunger, Tim?

TIM:

Her words shot out. She seemed flustered.

Oh, äh, ja, habe ich, mein Schatz.

I replied confused, half answering Emma and half smiling at her grandfather. She suddenly seemed to be much more anxious than I was. Lukas then joined the conversation.

LUKAS: Toll, ich habe auch Hunger. Worauf hast du Lust? Isst du gerne Gemüse oder lieber Fleisch?

TIM: Ich mag beides.

I responded.

LUKAS: Cool! Und hat meine Schwester dich schon in die deutsche Küche eingeführt? Isst du gerne Schnitzel oder Sauerkraut?

TIM:

The food all sounded great, but why were you ignoring their relatives, I wondered to myself.

Ja, ich mag alles.

I replied, then attempted a return to their grandfather. But Emma swept in once again with:

EMMA: Cool, dann setz dich doch zu Lukas und mir. Das Essen sollte bald fertig sein.

HELENA: Oh, poor Tim!

DANIELLE: Poor Tim! And the really funny thing is that he thinks he’s killing it. He’s like, oh, man, I’m really good in this family thing. And it’s like, no, Tim.

HELENA: No, Tim, you’re reading the signs wrong. But I’m sure his enthusiasm was infectious.

DANIELLE: Oh, yeah, I’m sure they enjoyed that, right?

HELENA: Yeah, they were so polite, too. It reminds me just of these German families I met. They’re like, okay, what the heck? “Hoppla, habt ihr schon was getrunken?” You know what that means?

DANIELLE: Yeah, he totally didn’t catch that. So, they asked, “Are you already drunk?”

HELENA: Yeah, or it technically means “Did you already drink something?”.

DANIELLE: Oh, “betrunken” is also drunk, right?

HELENA: No, he said, “Habt ihr schon was getrunken?”

DANIELLE: Ach, getrunken.

HELENA: Yeah.

DANIELLE: Oh, okay.

HELENA: This is why, please, be really careful, because you have “betrunken”, which means really drunk.

DANIELLE: Really drunk.

HELENA: Then you have “getrunken”.

DANIELLE: Getrunken.

HELENA: Which is…

DANIELLE: Have you drank?

HELENA: Yeah.

DANIELLE: Or have you drunk, actually. Sorry.

HELENA: And not to be confused with “ertrinken”.

DANIELLE: Ertrinken.

HELENA: Which means to drown.

DANIELLE: Oh, okay.

HELENA: Yeah. When Tim greets Emma’s father, Johann, he says, “Hi, ich bin Tim, und du bist sicherlich Johann. Ich freue mich sehr, dich kennenzulernen.” And then Johann responds with, “Ach, wir sind schon beim Du, was?” Did you understand that part?

DANIELLE: No, I didn’t.

HELENA: “Wir sind schon beim Du” means, oh, we are already at an informal way of speaking to each other.

DANIELLE: Oh, because he said “beim Du”.

HELENA: Yeah, so we’re already doing… we’re “duzen” each other.

DANIELLE: Oh, okay, so we’re already there. All right, okay, I didn’t catch that part. There was… I understood sort of the…

HELENA: Yeah, which is, honestly, a mean joke of Johann.

DANIELLE: Yeah.

HELENA: Because, honestly, that’s really nerve-wracking. I never know if to use “du” or “Sie”.

DANIELLE: Right.

HELENA: And people are really different. Sometimes, they’re like, oh, we’re family, you go straight to “du”. And sometimes, it’s like, nah, you have to earn my trust and earn your place in our family, so it has to be “Sie” first.

DANIELLE: Well, he is Emma’s dad, right? So, he also kind of has to kind of be a little bit cheeky with the boyfriend of his daughter, I think.

HELENA: Yeah, there has to be a little bit of stress.

DANIELLE: Yeah, it’s like I have to haze you just a bit.

HELENA: Yeah, well, Tim, because he’s so enthusiastic and, might I say, oblivious to social cues, he…

DANIELLE: He’s like, huh?

HELENA: He just brushes that one off. He’s like, oh, it doesn’t matter.

DANIELLE: We’re good.

HELENA: But then Johann says, “Das war nur ein Scherz.”

DANIELLE: “Scherz” is a joke.

HELENA: Yeah, that was just a joke. “Willkommen in der Familie, Tim.”

DANIELLE: Okay.

HELENA: So, Johann actually…

DANIELLE: Welcome to the family.

HELENA: He’s got a good humor and he’s very welcoming.

DANIELLE: Oh, that’s sweet!

HELENA: So, then Julia comes in, which is Emma’s mom, the birthday queen, and Tim greets her with saying happy birthday. How do you say happy birthday, Danielle?

DANIELLE: Okay, it’s a lot of German syllables. Herzlichen Glückwunsch zum Geburtstag!

HELENA: Ja, herzlichen Glückwunsch zum Geburtstag.

DANIELLE: Okay, yeah.

HELENA: There’s an easier way of saying it, though.

DANIELLE: How can I say it?

HELENA: Alles Gute!

DANIELLE: Oh, that’s the one I know and love. Alles Gute, yeah, alles Gute.

HELENA: Yeah, you can say “alles Gute” or you can say “alles Gute zum Geburtstag”. Both work, but the short phrase is “alles Gute”.

DANIELLE: Alles Gute.

HELENA: Which means everything good.

DANIELLE: Oh! Which is a very nice way to wish someone happy birthday.

HELENA: Yeah, best wishes. Herzlichen Glückwunsch — that’s a way of saying…

DANIELLE: To have luck?

HELENA: No, “Glück” also means…

DANIELLE: Happy?

HELENA: Happiness.

DANIELLE: Happiness.

HELENA: This is like the funny word, “Glück”, in German, which means happiness and it also means lucky. It’s a fairly interesting combination of concepts that are in one word.

DANIELLE: Because I almost… I guess if I were to know the words in German, I would maybe wanna say like “frohe Geburtstag”, like happy birthday, literally.

HELENA: Okay, that doesn’t translate in that sense. You basically are congratulating somebody on their birthday.

DANIELLE: I see.

HELENA: So, you’re not saying happy birthday like you would say happy Christmas or something. You’re saying it’s a congratulations to your birthday.

DANIELLE: Oh, okay.

HELENA: Which is where the “Glückwunsch” comes in.

DANIELLE: Okay, interesting.

HELENA: But you would say, for example, “frohe Weihnachten”, which means happy…

DANIELLE: Happy Christmas.

HELENA: Happy Christmas. Frohes neues Jahr.

DANIELLE: Okay, happy new year.

HELENA: Or “frohe Ostern”.

DANIELLE: Okay, happy Easter.

HELENA: Yeah, so Tim has finished greeting everybody on the forehead, and Emma is trying to pull him away from…

DANIELLE: Right.

HELENA: Her grandfather.

DANIELLE: Because she doesn’t want him to go in for that kiss on granddaddy.

HELENA: And so, a really effective distraction is Emma asks Tim, “Hast du Hunger?”

DANIELLE: Okay, so are you hungry?

HELENA: Yes, and the answer to that is, yes, I’m hungry. It’s right before lunch. Hast du Hunger, Danielle?

DANIELLE: Ja, ich habe Hunger.

HELENA: Wir haben alle Hunger hier.

DANIELLE: So, it’s like “I have hunger” instead of “I am hungry”.

HELENA: Yes.

DANIELLE: Okay.

HELENA: Because “Hunger” is a noun.

DANIELLE: Oh, okay, yeah.

HELENA: But if you wanna make it the adjective way, you would say “ich bin hungrig”.

DANIELLE: Oh, okay.

HELENA: But not as commonly said.

DANIELLE: Okay, good to know.

HELENA: Yeah. Lukas, the brother, he says, “Worauf hast du Lust? Isst du gerne Gemüse oder lieber Fleisch?”

DANIELLE: Oh, okay. “Hast du Lust?” So, what do you love or what do you want or…

HELENA: So, “Lust” basically means to be in the mood for something.

DANIELLE: I see.

HELENA: It’s like you want to do something.

DANIELLE: Yeah, I always get a little bit confused when I hear or see the word “Lust” because I want to… I think about lust in English.

HELENA: Oh, lust!

DANIELLE: Yeah, which is also kind of a word that’s kind of hard to pin down, isn’t it?

HELENA: Yeah, it’s more passionate.

DANIELLE: Exactly.

HELENA: “Lust” is pretty neutral actually.

DANIELLE: I see.

HELENA: Yeah, it’s like “What do you want?”, you can say. But what’s interesting about “Lust” is there’s also this word “lustig”.

DANIELLE: Lustig, yeah.

HELENA: Which means funny.

DANIELLE: Funny.

HELENA: So, there you go German! Why are you making all these confusing words about happiness?

DANIELLE: Okay, so “worauf hast du Lust” is like what are you in the mood for?

HELENA: Exactly.

DANIELLE: Okay, good.

HELENA: So, they decided they’re gonna eat. And Emma tells Tim where to sit. She says, “Cool, dann setz dich doch zu Lukas und mir.”

DANIELLE: Okay.

HELENA: So, interesting little detail here. She says “setz”.

DANIELLE: Setz. Is it similar to “sitzen”?

HELENA: Yes, she doesn’t say “sitzen”, “sitz da”. She says, “setz dich dort”.

DANIELLE: Oh! Why?

HELENA: Because in German you have two different verbs for sitting. You have one that describes if you’re standing and where to sit.

DANIELLE: Okay.

HELENA: So, setz dich dahin. And then you have the “sitzen”, like “ich sitze hier”, where you are sitting there; I’m sitting here.

DANIELLE: Oh, okay, interesting. So, there’s sort of the active sitting and then the sitting itself.

HELENA: Yeah.

DANIELLE: Oh, okay.

HELENA: Let’s listen to the next dialogue.

TIM: Was glaubst du? Wie läuft’s denn?

EMMA: Tja...

TIM

Emma started, but I wanted to assure her.

Falls du dir Sorgen machst, die Nerven sind weg. Ich glaube, es läuft gut, oder?

She looked hesitant for a second, but then agreed. It seemed she wasn’t over her own nerves yet, but as the day proceeded, it became better than I could have ever expected.

Glaubst du, sie mögen mich?

I asked.

EMMA: Sie lieben dich.

TIM:

She said softly, but clearly still uneasy.

DANIELLE: The story just went from really funny to like, oh, this is getting a bit sad.

HELENA: Well, not sad, it’s getting… Tim’s being brought down to earth. Let’s put it that way. It’s like, oh, Tim! He’s like, “Die Nerven sind weg. Ich glaube es läuft gut, oder?” He’s like, it’s going great.

DANIELLE: This is going so good!

HELENA: And she’s like, I don’t… She’s…

DANIELLE: Well, I think she feels, at this point, she probably feels like really bad.

HELENA: Yeah, like, oh, man, I set him up and now I gotta tell him, break the news to him.

DANIELLE: Yeah, true.

HELENA: Yeah, but she still doesn’t do it then. So, she says… At the beginning, Tim asks, “Was glaubst du? Wie läuft’s denn?”

DANIELLE: So, it’s like, what do you think? How is it going?

HELENA: Yeah, exactly. Wie läuft’s? That is a pretty common thing to say in German.

DANIELLE: Wie läuft’s?

HELENA: You can say “Wie läuft’s?”. Like, what’s going on?

DANIELLE: Because “laufen” means to walk.

HELENA: Yeah, maybe more easy translation is “it goes”. How’s it going?

DANIELLE: How’s it going, okay. How’s it going?

HELENA: Think it’s going well?

DANIELLE: Yeah, was glaubst du?

HELENA: That means “what do you think” or “what do you believe”.

DANIELLE: What do you believe?

HELENA: Yeah, and then, also with the “glauben”, Tim asked, “Glaubst du, sie mögen mich?”

DANIELLE: Do you believe they like me?

HELENA: Yeah.

DANIELLE: Oh!

HELENA: And she says, “Sie lieben dich.”

DANIELLE: Oh, they love you!

HELENA: Yeah, there’s one more fun word in this little short dialogue. It’s “tja”.

DANIELLE: Tja. What is “tja”?

HELENA: Tja, spelled t-j-a, teh-jot-ah.

DANIELLE: Teh-jot-ah, tja.

HELENA: Tja, tja, tja, I always say “tja”.

DANIELLE: Tja — What does it mean?

HELENA: Tja — it can mean “well” or “yeah”.

DANIELLE: Yeah!

HELENA: Or “tja” just means “that’s how it is”.

DANIELLE: Okay.

HELENA: It’s another one of these filler words that has a lot of purpose.

DANIELLE: I see.

HELENA: A lot of different meanings, depending on the situation.

DANIELLE: But saying it would make me sound like I actually speak German, right? Tja!

HELENA: Yes.

DANIELLE: Okay.

HELENA: Add that one to the vocabulary.

DANIELLE: Okay.

HELENA: You have “tja” and you have “genau”.

DANIELLE: Jein.

HELENA: “Jein” and “genau”.

DANIELLE: Genau, yeah.

HELENA: “Jein” is the combination of yes and no.

DANIELLE: Oh, yeah, you “jeined” me earlier, didn’t you?

HELENA: I did.

DANIELLE: I caught it, but I was like, I’ll let that go.

HELENA: To be brought up later in the discussion. So, let’s listen to the next dialogue then.

DANIELLE: Okay.

JULIA: Es ist so nett von dir, dass du den ganzen Weg hierher gekommen bist, Tim. Wir freuen uns sehr, dich endlich kennenzulernen.

TIM:

She then walked across the lawn to me and placed her hands on my shoulders, rising up so we were level. She kissed me on the forehead and smiled. It was then that I recognized the heartfelt significance of their tradition. As we strolled towards the house, I turned to Julia.

Mir war nicht klar, dass man sich auf die Stirn küssen kann nicht nur um hallo zu sagen. Wann kann man es sonst noch tun?

Julia had used the greeting as a way to comfort me. Perhaps I could do the same for Emma? But then…

JULIA: Ich weiβ es nicht. Wann kann man es tun?

TIM:

Maybe I was misunderstanding her.

Entschuldigung, ich meinte die traditionelle Begrüβung aus deiner Stadt.

I explained.

JULIA: Aus meiner Stadt? Ich dachte, du sprichst davon, was bei dir Sitte zu sein scheint. Ein Kuss auf die Stirn, nicht wahr?

DANIELLE: So, Tim is finally realizing. It’s becoming clear.

HELENA: Yeah, this dialogue is an exchange between Tim and the mom, Julia, and, at this point, they’re like — Wait, what?

DANIELLE: Wait, what? Julia’s so sweet.

HELENA: Yeah, she is really sweet. She kisses Tim on the forehead, and Tim was thinking maybe it’s a way of her comforting him. And he says then, “Mir war es nicht klar, dass man sich auf die Stirn küssen kann nicht nur um hallo zu sagen. Wann kann man es sonst noch tun?”

DANIELLE: Oh, that’s a lot! I actually did not catch the full meaning of that.

HELENA: Yeah, let’s break that down a little bit. “Mir war nicht klar.”

DANIELLE: It’s not clear to me.

HELENA: Oh, yeah, I didn’t know or it wasn’t clear to me. “Dass man sich auf die Stirn küssen kann.”

DANIELLE: That you can kiss someone on the forehead.

HELENA: Uh-huh. “Nicht nur um hallo zu sagen.”

DANIELLE: And not only just saying hello.

HELENA: Yeah, not only to say hello. Because she did it to comfort him.

DANIELLE: Right, right, okay.

HELENA: And then she was like — Äh?

DANIELLE: Äh, was? Ich weiβ es nicht.

HELENA: He’s like, “So, when else can you do it?” And she’s thinking it’s his tradition. She’s like, “You tell me, okay?” But it’s really nice because they have now made this tradition in their family…

DANIELLE: Yeah, sure.

HELENA: As a way to say hello to each other and to comfort each other. So, it’s really nice to see when mistakes turn into something really positive in the end.

DANIELLE: Yeah, or mistakes turn into a nice inside joke, right? That’s just that they only share, and so that’s really nice. That’s when you know that you’re really like kind of connecting with someone when you have these.

HELENA: Yeah, part of the family.

DANIELLE: Yeah, sure.

HELENA: Then, Julia’s like — Uh, what? And Tim’s like, “Entschuldigung, ich meinte die traditionelle Begrüβung aus deiner Stadt.”

DANIELLE: Oh, excuse me, but this is the tradition of your city.

HELENA: Yeah, pardon, I thought this was your tradition.

DANIELLE: Oh, okay, yeah.

HELENA: And Julia is like, “Aus meiner Stadt?” Nah.

DANIELLE: No, no, no.

HELENA: So, the “Kuss auf die Stirn” is now the family tradition.

DANIELLE: Oh, it’s very sweet. And the kiss on the forehead is very endearing actually. Like, my grandmother always used to kiss me on my forehead. So, I actually have a very nice association with that gesture.

HELENA: Yeah, it’s very intimate.

DANIELLE: It is.

HELENA: But in a non-imposing way.

DANIELLE: Yeah, I think so, yeah.

HELENA: Well, that’s it, Danielle. We’ve gone through all the dialogue, and I hope everyone now can understand everything a little bit better.

DANIELLE: Great!

HELENA: See you next week! Bye!

Grammatically Speaking

[44:00]

HELENA: So, as you guys know, I am not an official language teacher, but we have our two wonderful teachers, Stefie and Inda, in house today.

STEFIE: Hey!

INDA: Hey, Elena!

HELENA: Hey, girls! So, let’s talk a little bit about a theme that has come up a few times in past podcasts, this difference between “du” and “Sie”, the difference between addressing somebody formally and addressing somebody informally. So, as we mentioned earlier in the breakdown, there’s this incident where Tim refers to Johann, Emma’s father, informally.

STEFIE: Oh, yeah, choosing between “du”, the informal “du”, and the formal “Sie” can be tricky. Even after a lot of practice, even after years of studying German, you could still make that mistake because it’s not straightforward when you use it.

INDA: It’s a real dilemma, and I would say there is no right or wrong in a lot of cases. There are a lot of gray areas, and even native speakers will struggle with choosing one or the other.

STEFIE: Exactly, but you could say you use “Sie” in a formal setting.

HELENA: So, why don’t we go over some scenarios where you would use “du”and where you would most commonly use “Sie”?

INDA: I would say that understanding the difference between the formal and informal usage is a little bit of culture, so, first of all, understanding Germans are a little bit more distant to someone that they don’t know very well. And that’s a good rule of thumb to start with. If you don’t know someone, if you just met them, you usually go by “Sie”, unless, of course, they are the same age as you.

HELENA: Or younger.

INDA: Or younger, right. But if it’s a formal setting in maybe more traditional business contexts, then you would use “Sie” regardless of the age, really.

STEFIE: Yeah, so maybe… But at the start, for example, I guess you would use… Well, maybe you would speak in English as well, but you would use “du”, I guess. I guess you have to maybe wait to see what the others use and then use the same. And it’s, also, you also have regional differences, I think. I studied in Freiburg, and I even used the “Sie”, the formal “Sie”, when addressing, for example, a waiter or a waitress who was my age and who I knew from school actually, from university. Like, they weren’t friends, but I just knew who they were; I saw them once in a while. But you would just still use the “Sie”. And I think I wouldn’t do that here in Berlin.

HELENA: Yeah, I’m always confused if I should address somebody who’s my own age — at a restaurant, or like a bakery, or across the counter from me — with “du” or “Sie”. I’m kind of inconsistent with that. Sometimes I use one or the other.

INDA: Well, actually, I think there is a pretty consistent rule there. Like, people working in customer services or in general service, you would use “Sie”, unless you know them, right? Like, maybe you are a customer that comes every day or something. Then, you already know their name, and you had small talk with them. Then, probably, you would move on to the “du”. Otherwise, you would use “Sie” no matter their age.

STEFIE: Yeah, and, I guess, also if you go to a doctor for example.

INDA: Exactly.

STEFIE: You would use “Sie”. Or if you’re talking to your professors, I guess, you also use “Sie”, right?

INDA: Definitely, most certainly teachers and professors.

HELENA: Teachers at school, you think, as well?

STEFIE: I guess it depends, right?

INDA: On the age.

HELENA: I use “Sie” for my teachers in Germany.

INDA: In most schools, unless they are kind of maybe a different kind of… Waldorf school or…

STEFIE: I mean, at my school, I think when we were doing our Abitur, like when we were 18 or 19 even, we used “du” at some point. That’s a bit ridiculous; you see all the time. We were adults.

HELENA: Yeah, I remember having a hard time using the “Sie” form when I was in German school. Sometimes, I would go with my friends to take like a class with them, and because I only ever spoke German with my family, I never had to have this experience of using the “Sie” form. So, I would sometimes address the teachers with “du” and they didn’t like that.

STEFIE: Yup.

HELENA: But it was really hard for me to switch my brain over because you don’t have it in English.

INDA: Right, sometimes it can be taken as a sign of disrespect. And this is, I think, a general rule of thumb. If you’re in doubt, just use “Sie” because that’s a safer side. And people might offer you “duzen” — “duzen”, which means to address someone with du — if they are like, oh, you don’t have to… you don’t have to call me by “Sie”, and you can say “du” to me.

STEFIE: Yeah, and I think another tip is what I said before, just listen and adopt. Like, listen to whatever everyone is saying in that context and just use the same.

HELENA: I see.

STEFIE: Before. But, yeah… Okay, but Tim, in this case, was very straightforward and he just wanted to talk and he…

INDA: But, you see, I mean, okay, the father didn’t take it that badly, so he made a joke about it. He understood. That’s, I think, also a bonus point for being a learner, right? Like, no one will probably think you’re being disrespectful. They probably know that you’re just struggling with the wrong form. But, I mean, if you’re talking to a police officer, you should definitely use “Sie”.

STEFIE: Yeah, exactly. You told me the other day a story about saying “du” to a police officer, that you could get into trouble.

INDA: Right. I mean, right, they can give you a fine.

HELENA: What?

INDA: A 500 euro fine if you say “du” to a police officer.

HELENA: Oh, my gosh!

INDA: Yeah, there is such a thing. Actually, there was this very famous case. You know Dieter Bohlen, the singer? He’s a big figure in German television and music business. He had a conversation with a police officer in the street, and he said “du” to the police officer. The police officer was so offended that he took him to court. And, obviously, that case was very famous and it came in television. And the judge eventually decided in favor of Dieter Bohlen because, well, he argued that, in his business world, in the television business, the “Sie” form is so old school that no one ever uses it. So, he got away by saying, basically, “I never use that in my job. I never use that with my friends or family, so I’m just not used to that anymore.”

STEFIE: He was basically saying — I’m just too cool…

INDA: Right.

STEFIE: To use the “Sie”.

INDA: So, and the judge was like — Okay, you can go out without a fine. It’s fine.

HELENA: Wow, I find that really hard to believe, if he grew up speaking German, that he doesn’t know the “Sie” form.

INDA: Of course, he did it deliberately.

STEFIE: He just doesn’t want to use it.

HELENA: It’s like, that’s a publicity stunt.

STEFIE: He just doesn’t want to use it, I guess. He’s interesting.

INDA: Yeah.

STEFIE: But, I guess, the “du” form is winning territory over “Sie”.

INDA: Definitely, younger people are preferring more and more to use “du”. And, I mean, there are some cases where you clearly should use “du”. For example, when you meet someone at a party that is rather informal, or a networking event, or a bar, just because it’s a stranger, you shouldn’t talk to them with “Sie”. That would be weird.

HELENA: I find that I use “du” when I’m referring to cafe baristas that are my own age. I feel like that maybe it’s just a Berlin thing, but I feel really weird “siezen”, “Sie”, like using the formal form for people my own age who are kind of like… I feel like cafes are kind of almost informal. Even though it’s an exchange, that’s where I get most confusing. Okay, you’re my own age; we both know that we’re doing like a chill job here.

STEFIE: Sometimes, when I’m not sure, I just avoid conjugating, like using “du” or “Sie”, and just like, “Einen Kaffee, bitte. Vielen Dank.” You don’t have to say anything else, right? I was wondering, actually, how is it in English? Is it a two-way street? For example, if you’re saying Mr., I don’t know, Fox, your professor…

INDA: Or your boss.

STEFIE: The philosophy professor, I don’t know. Will he say Mrs. Balint as well? Would he use the formal…

INDA: Would you ever have the situation where one person addresses with Mr. and the other person doesn’t? Addresses with the first name.

HELENA: Yeah, actually, there would be that case. I remember — because I grew up; my mom’s German — I had a lot of German friends. And their moms are all German, too. And I remember I would always call their moms’ names by their first name. And because I didn’t have very many American friends, when I would go into an American household as a kid, I would call their mom by their first name.

INDA: Right.

HELENA: And they actually got offended by that, and I once got corrected. They’re like, “Actually, it’s Mrs.”

STEFIE: Oh!

HELENA: And I was like, “What?”

INDA: But they will tell you Helena.

HELENA: Yeah, but they refer to me Helena.

INDA: Right.

HELENA: They don’t call me Ms. Balint. That would be bizarre. Or in the school setting, you say — Hey, Mr. and Mrs. Shack. That was my first-grade teacher. They would not call me Ms. Balint, no.

INDA: Right, I would say that’s a very interesting difference in German, because, in German, it’s always a two-way street.

HELENA: Except for adults and children, right?

STEFIE: Yeah, it’s like…

INDA: It’s reciprocal.

STEFIE: If you meet your partner’s parents, you would use “Sie” instead, and they would call you by your name. And in Germany, it’s a two-way street, right? So, they would use “Sie”. And I find that’s so weird. I know I have a friend, and she was complaining actually because she had been with her partner for seven years — I don’t know how long — and the parents would still “siez” her.

HELENA: Oh, my gosh, that’s awful!

STEFIE: And, yeah, she actively complained about that.

HELENA: That’s, basically, like saying you’re not in our family.

STEFIE: Yeah.

HELENA: We’re rejecting you.

STEFIE: Imagine Tim, like, after two seconds uses the “du”.

HELENA: Yeah.

STEFIE: He was lucky.

HELENA: Yeah. I noticed that, in German, sometimes, when you’re saying… Okay, you’re addressing somebody the formal way and you’re saying “Frau Müller” for example. And then she responds with saying, “Nein, nein. Anita,” for example. Like, “Call me by my first name.” That signifies automatically that you’re then switching to the “du” form, the informal, correct?

INDA: Yeah, yeah.

STEFIE: Yeah.

HELENA: That’s also so similar in English where if you say “Mr. and Mrs. Smith” and they’re like, “No, please call me Jane”…

INDA: Right.

HELENA: Then you know you’re on the informal basis.

INDA: Yeah, you don’t have a verb for that, right? Well, in German, usually here people say like, “Oh, du kannst mich duzen.”

HELENA: Yeah.

STEFIE: Yeah, it usually happens. So, sometimes… Of course, if you go to the doctor’s, you would always use “Sie”. But sometimes there are people you always use “Sie” with, and it’s so weird that you keep doing that after like years of knowing them or after having like a closer relationship to them, and you still use “Sie” just because they haven’t offered. And they’re maybe older, so you have to wait. Sometimes, I wait, and wait, and it doesn’t happen. Like, why?

HELENA: Yeah, I guess. So, it’s difficult sometimes to know, but, yeah, you have to wait for the permission.

STEFIE: You have to wait for that, yeah.

HELENA: Yeah, I made the mistake with one of my grandmother’s friends once where I “duzt” her and she was not having it.

STEFIE: After that, you didn’t get more cake.

HELENA: No, basically. I was like… Okay, so my thought process was — She’s a friend of the family, like a close friend of the family. That means that she’s basically family, which means she’s my family, which means I would use the informal form.

STEFIE: Nah, nope.

HELENA: No.

INDA: Yeah, yeah, that’s why I always recommend everyone to use “Sie”. If you have to think about it, then just go with the “Sie” because, I mean, in other cultures, being too formal or being too distant is a bad sign. It’s going to be interpreted as something almost rude. In Spanish, for example, if you’re too distant, people are maybe going to be offended. In Germany, or at least the context I’ve been in contact with, people are not offended by you being too formal. That’s not necessarily something that is gonna cause any friction. But if you’re being too informal, that’s probably the tricky one.

STEFIE: And, plus, the good news are that, when you conjugate “Sie”, you don’t change the verb — Sie essen, Sie schreiben.

INDA: Right, we should talk something about grammar — conjugation.

STEFIE: Yeah, the conjugation is — Just don’t change anything.

INDA: Right.

STEFIE: So, please, yeah, use the “Sie” every time.

HELENA: “Sie” plus the… What is that form of the verb called?

INDA: Well, it’s always the same ending as the infinitive.

HELENA: The infinitive, right.

STEFIE: So, it looks exactly the same — Sie essen, Sie schreiben, Sie trinken.

HELENA: Yeah, that’s really easy.

INDA: It’s a beautiful, beautiful conjugation. And it’s always regular, with one exception.

HELENA: Which one?

STEFIE: Sein.

INDA: Sein — Sie sind.

STEFIE: Sie sind.

INDA: Right, it’s the only irregular.

HELENA: So, if you’re unsure if it’s formal or not and if you’re unsure of how to speak German, use the “Sie” form.

STEFIE: Exactly.

INDA: And if you’re talking to a police officer.

STEFIE: Yes, please.

HELENA: Well, that’s a wrap. Vielen Dank to Danielle, Inda, and Stefie for joining us today. And a special thank you to our actor Sam Peter Jackson for his reading of this episode. If you’re following along with Chatterbug’s curriculum, you can find the links to this episode’s topics in the podcast notes and on Chatterbug’s blog. Long Story Short is from Chatterbug and produced by Weframe Studios. We’ll have a new story for you next week. I’m Helena, bis dann. Tschüss!

Want to learn more?

If you’re feeling inspired, sign up below for a free Live Lesson with a private qualified tutor to start speaking a new language for real! Our classes are structured around exercises created by language teachers, so there’ll be no awkward silences – we promise! 😉