Growing Up As A Third Culture Kid

With the rise of globalisation and the increasing opportunities that come therewith, a growing number of families are choosing to work and live in a foreign country. Parents settle into their new surroundings and work schedules, send their children to the local school or daycare – this is the expat life familiar to many. But further down the line, where do their children end up calling home?

When I was three years old, my parents decided to relocate from England to Germany, as they had lived there for a substantial part of their adult lives, working in music and the arts. Germany had more work opportunities for them at the time, and raising a family up in the Bavarian Alps seemed like a nice prospect. My two younger brothers were born in Germany, and there has never been any mention of moving back to England since.

A term that has not (yet) made it into everyday use in this context, and one which I believe deserves more exposure, is Third Culture Kid. Having grown up in Germany to English parents, this term and the research behind its development later helped me understand my circumstances better.

What is a Third Culture Kid?

Third Culture Kid, or TCK for short, is a term coined by US sociologist Dr. Ruth Hill Useem in the 1950s, for children who spend their formative years in places that are not their parents’ homeland. Her work focused on US-American children growing up in India, after spending a year on two separate occasions in India with her three children, and was the first to identify common themes among various TCKs that affect them throughout their lives.

TCKWorld defines the term as such: “A third culture kid is a person who has spent a significant part of his or her developmental years outside their parents’ culture. The third culture kid builds relationships to all the cultures, while not having full ownership in any. […]”

I came across this term while on a Wikipedia binge (don’t ask) many years ago. It encapsulated how I was feeling at the time astoundingly well. I was too English to be German, too German to be English, and yet did not feel particularly strongly about either of those cultures. Unlike other children of immigrants I had met throughout my childhood, I never saw nationality as an integral part of my identity. I was never a “proud Brit” (especially not in light of recent events). Even after I attained my German citizenship (after aforementioned events) I did not feel “Deutsch und stolz darauf” either. Belonging to two cultures but simultaneously feeling disjoined from both of them led me to just accept that I do not, and probably will not, feel a sense of belonging to either.

TCKs move between cultures before they have had the opportunity to fully develop their personal and cultural identity. The first culture of such individuals refers to the culture of the country from which the parents originated (in my case England), the second culture refers to the culture in which the family currently resides (Germany). Although not widely agreed upon by the TCK community, some sources refer to the third culture as the amalgamation of these two cultures. I personally agree with this description.

No matter the reasons for your family’s move, the crux of the matter is that your home and host nation form separate spaces in your life.

How was it growing up as a Third Culture Kid?

Although we lived in Germany, the household I grew up in was still very English. We ate Marmite on toast for breakfast, my parents drank copious amounts of black tea with milk, Mum read Enid Blyton books and sang nursery rhymes to us. I am not sure how (as streaming did not exist then) but we also watched a lot of English cartoons and TV shows. We, to this day, celebrate Christmas on the morning of the 25th, unlike Germans who celebrate the night before. My parents both speak German fluently, however we never speak German to each other. German was the outside world beyond the safety of our loving home.

Taking this into account, I never considered myself “raised bilingual” since I didn’t learn German from the beginning. I’m bilingual as a result of my family’s living situation, I was just lucky enough this change came about when I was very young.

How did you learn German then?

“So you’re fluent in English and German? You’re so lucky,” many often swoon, “I wish my parents had brought me up bilingual.”

Indeed, I am bilingual, however that doesn’t mean I have two native languages. I have made a point of emphasising that I wasn’t raised such. I was thrust into my German-learning journey at the age of four when I had to attend kindergarten. Struggling to conquer the art of Basteln and complicated games like “House” or “Doctor”, I was forced to deal with a lot of frustration and communication barriers from a young age. Moving on to school after kindergarten, my mother would patiently help me with homework, translating the questions and, in turn, my answers. Fast forward, I successfully passed high school and went on to study at a German university, all in German.

Needless to say I was thrown in at the deep end. However, I later came to realise that I had learned a lot more than just a language. Not to mention my spoken and written German is at a level that can be mistaken for a native speaker (it is only when I mention my heritage I am told I have an accent, go figure). Along with enhanced problem-solving skills, I gained the ability to filter information quickly and switch between languages almost seamlessly. I go deeper into the benefits of being bilingual in another post you can find here.

This brings me to another point…

What are the benefits (and challenges) of being a TCK?

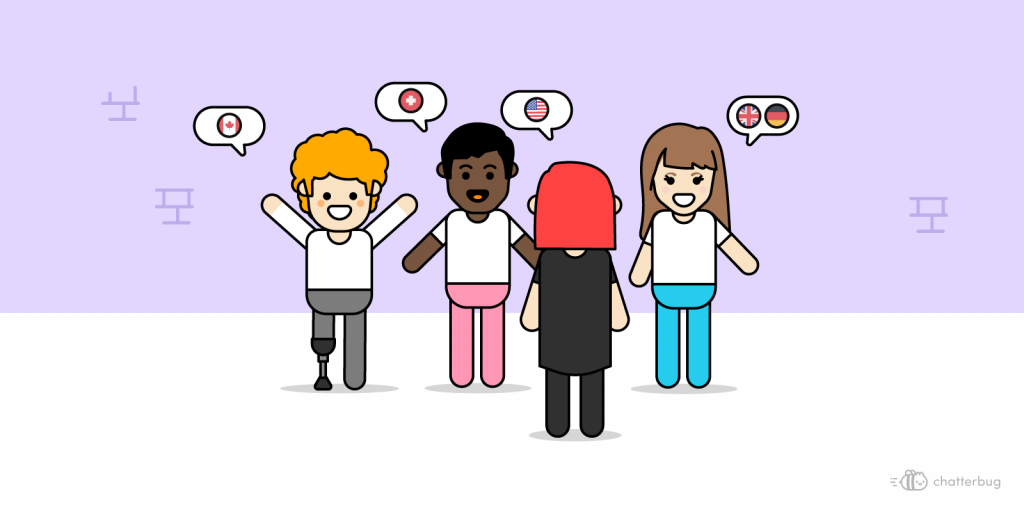

It goes without saying that growing up or raising a child in a foreign country is hugely beneficial in many ways. Apart from the obvious major benefit related to language exposure, TCKs develop an expanded worldview early on, with an understanding that there is more than one way to look at a situation. Through prolonged exposure to native language use, they can learn to see themselves through the eyes of others. Interpersonal sensitivity is increased as a result of being exposed to a variety of lifestyles and perceptions early on. They can register societal norms and cues more adeptly and thus have an openness to others.

This in turn leads to a cross-cultural competence, or cultural intelligence, which opens up a wealth of opportunities in both work and life. TCKs can function very effectively across cultures. A higher level of general adjustment is often noted in comparison to mono-cultural individuals.

The benefits greatly outweigh the challenges in my opinion, but I can only speak for myself. It is important to recognise that each individual TCK is faced with a unique set of challenges due to a number of factors. It is, in my opinion, somewhat unfair to lump all TCKs into one homogenous group. Third Culture Kids is an umbrella term to describe military brats, missionary kids, diplomatic kids, and business kids. In recent years, children of refugees have also been included in this list. Scores of books have been written on Third Culture Kids, “Global Nomads”, and military brats based upon the concept originally proposed and defined by Dr. Useem and research on these groups of children continues.

This is a good segue into the challenges a child can be faced with when growing up in a culture other than their family’s. Third Culture Kids can experience a lot confusion with politics and values. This issue is also related to the identity crisis, on a cultural level, of not being able to feel a sense of oneness with any one nationality or culture. Oftentimes, TCKs cannot answer the question: “Where is home?” This is not helped by an often reported ignorance of one’s home culture, and re-introduction upon returning to that country can prove difficult. Feelings of rootlessness and restlessness can also make the transition to adulthood a challenging period for TCKs (which is worth mentioning for the parents out there).

Upon reflection, I can say I have both benefited and struggled with these points. The “rootlessness” has played in my favour on a number of occasions, though I cannot deny that I have sometimes secretly longed to feel some kind of sense of patriotism, however ridiculous that may sound. To the contrary, however, I have also embraced this limbo as a way to remain impartial and to some degree detached, making it easier for me to evaluate almost everything in life from more than one angle. In regards to the debate around what the “third culture” stands for, I personally believe that my cultural identity manifests in a concoction of both. This is partly due to language, since one’s brain is wired differently when speaking different languages, but I do my best to be the bridge between and the amalgamation of the best of both English and German culture.

Final thoughts

This is an appeal to incorporate the term Third Culture Kid into our conscious vocabulary. Globalisation has made us TCKs more commonplace in an increasingly diverse global community. A growing understanding of that can help children — who have changed schools numerous times, had to quickly learn one or more languages, had to adapt to a new set of circumstances, and say far too many goodbyes — to feel more supported.

If you are currently raising, or planning to raise, your child in a foreign country, it helps to understand that while they are very adaptable and seem to absorb language like a sponge, it does not mean these changes do not have a lasting effect on them. Encouragement and unshakeable support are necessary to help navigate the strange outside world that contrasts so greatly to the family home. The aspects of parenting to a TCK may have to be saved for another post.

As an adult, I have come to greatly appreciate the closeness I have to my parents and siblings, and as a result of growing up in two cultures, I realise now how many valuable life skills I learned in my formative years. The thing I once bemoaned as an adolescent I now value as a great privilege.

If you yourself are a Third Culture Kid, I hope this helps put into words a few of the things you may have experienced or have struggled to define. Not that I go about wearing “Hey, I’m a Third Culture Kid!” as a badge of honour, I simply found it reassuring to discover that studies were done and a term developed to describe my and many others’ situation. Being an angsty teenager in conservative small-town Bavaria is a tough time for anyone, but I found solace in knowing that feeling like I did not belong was a natural, explainable, and above all common part of it. Later on in life, my brothers and also many (international) friends I have made along the way have expressed the same feeling, a neither-nor existence between cultures, and were excited to hear there was a term to describe that.

“Expat never cut it for me, because we weren’t just on an extended family holiday,” a friend of mine aptly put it, and I couldn’t agree more.

Want to learn more?

If you’re feeling inspired, sign up below for a free two-week trial and a Live Lesson with a private qualified tutor to start speaking a new language for real! Our classes are structured around exercises created by language teachers, so there’ll be no awkward silences – we promise! 😉

And don’t forget to check out our Facebook, Twitter and Instagram pages for more language content!